328 Mickle Street: Walt Whitman in Camden

Diana Maddison

“Camden was originally an accident, but I shall never be sorry I was left over in Camden. It has brought me blessed returns.”[1] Walt Whitman wrote longingly of the city of Camden, where he spent the final years of his life. He loved, and wrote about the growing industry of the Camden Waterfront and the ferry rides, traveling from the newly industrialized Camden to the historical city of Philadelphia, enjoying the aesthetic of the trips which combined both engineering and nature. Walt Whitman is known as the great American democratic poet, most popular for his publications of Leaves of Grass[2]. Born in New York, and travelling on the east coast for most of his life, many overlook Whitman’s last few years living in Camden, New Jersey.[3] The Walt Whitman House, located near the waterfront, is a renovated memorial to the American poet who spent his final years in Camden. Its mission is to foster an appreciation of Walt Whitman through the preservation of his home. The museum and memorial, the Walt Whitman House in Camden, New Jersey, perpetuates learning and offers a memorialized environment, as well as an investment for the city of Camden, made possible through preservation from both state and national funding.

Walt Whitman was born on May 31, 1819 into a working class family in West Hills, Long Island to a carpenter and farmer, Walter Whitman, Sr. and Louisa Van Velsor. He was the second oldest to five brothers and two sister. At the age of eleven, Whitman stopped formal education yet still pursued personal education, visiting libraries and museums and engaging in debate-like discussions with superiors at work. In 1831, he apprenticed at the Long Island Patriot, a liberal working class newspaper, where at twelve years of age he contributed to the paper, having his first works published. By 1835, sixteen year old Walt Whitman became a journeyman printer and compositor in New York City, continuing to work for various newspapers from 1842 to 1849. Whitman’s earliest recordings of writing poetry for his Leaves of Grass dates as early as 1850, and in 1855, Whitman published the first edition of Leaves of Grass with his own money. Throughout the 1870’s and 1880’s, Walt Whitman compiled and published numerous versions of his life writings while living with his brother George in Camden. Whitman moved into 328 Mickle Street in Camden in April of 1884.[4] From then until his death from tuberculosis on March 26, 1892, Walt Whitman continued writing and revising his works, obsessed with the appearance of his written words in printed form. Whitman chose to spend his final years in Camden, where he felt a transcendental connection with the city’s synthesis between industry and nature.

328 Mickle Street, the building where Whitman would spend the last eight years of his life, holds a significant history for Walt Whitman, the city of Camden, and the community which memorialized their poet. 328 Mickle Street, now currently residing on Martin King Luther Jr. Boulevard, was first built in 1848, twenty years after the city of Camden was established. Built in Greek revival style, this wooden-framed house was a typical style of most Victorian middle-class homes.[5] This two-story house contained six modest rooms and a moderately sized garden in the backyard. After living with his brother George on the nearby Stevens Street since 1873, Whitman, at the age of sixty-five, purchased this house in April of 1884. This was the first home the great poet ever owned. After his death on March 26, 1892, Whitman’s devout friend, the lawyer, Horace Traubel was one of the first to recognize the need to memorialize the poet. Traubel petitioned the City of Camden to purchase the estate and dedicate it as a memorial to the life of Walt Whitman.[6] Although his petition failed, Traubel’s enthusiasm prevailed. The early efforts were mostly undertaken by friends and neighbors coming together to accumulate Whitman’s belongings. The Whitman House’s first major preservation effort began in 1919, when a local publisher named David Stern successfully campaigned to have the city of Camden buy the property and oversee it.[7] The ensuing Walt Whitman Foundation was the first academically and historically accredited preservation organization to oversee restoration; it worked to furnish the house with his accumulated belongings including his furniture and small artifacts as well as the famous deathbed of Whitman. After the poet’s death, the residence was reclaimed by Whitman’s brother, George, and then inherited by his niece, Jessie Whitman, who sold it to the City of Camden in 1921.[8] In 1923, the site opened to the public as a museum of commemoration to the American poet Walt Whitman, but was not recognized as a state historical site until 1947. In 1962, the Whitman house was declared a national historic landmark by National Parks and Services, and included neighboring houses as the “Whitman neighborhood” in the register of historic places in 1978.[9] The New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry began research for the complete restoration of the Whitman house in the early 1980’s and final restoration was completed in November of 1998 through funds provided by the State Historic Trust. The Whitman house is presently open to the public free of charge and hopes to create an interactive learning center and waiting area in the near future. Through communal activism and state and national recognition, the Whitman house remains open, cultivating avid minds through memorializing America’s renowned democratic poet.

The preservation of the Whitman house was funded and made possible through numerous organizations. The New Jersey Historic trust and the DEP Division of Parks and Forestry provided the first funding, amounting to $830,600.[10] Later funding was supplied by New Jersey Historic Preservation Bond Program in 1992 totaling $33,380.[11] Funds were given to the Whitman house under the jurisdiction of New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry, Camden, in order to shore the foundation, replace wood beams, repair wood and plaster and plumbing fixtures, repaint the interior and exterior, and apply wallpaper specially printed to duplicate the wallpaper recorded in historic photographs. Preservation of the Whitman house was completed with these funds, winning the Victorian Society in America’s Preservation Award as well as other awards from the Preservation Alliance of Philadelphia and the New Jersey Preservation Office.[12] Because of these funds and awards, the Whitman house has become the idealized restoration of its original condition. Without a perfectly historical environment, the Whitman house would not offer the same magnanimous memorialized sentiment that a monument or museum should portray, offering a historically accurate atmosphere of learning which evokes an appreciation for the great poet.

The Whitman house collection holds chestnuts of the historical remembrance of Whitman’s final years in Camden, offering learning environments for all ages and creating a milieu de mémoire, or an environment of learning. French historian, Pierre Nora, is known for his work on memory and identity. In his essay “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Nora distinguishes the difference between places of memory, “les lieux de mémorie,” and environments of memory, “les milieux de mémoire.” The disappearing of the past, due to generalized customs in conjunction with inevitable loss of memory itself, attempts self-reconstruction in “les lieux”, or places marked by history. These “lieux”, however do not always encourage environments of memory, “les milieux de mémoire.” In “les milieux”, history and memory coalesce, installing a “remembrance of the sacred,” where the past, present, and future merge simultaneously and eternally.[13] The accumulation of the pieces in the Whitman house collection create a milieu de mémoire of Whitman and his legacy.

A series of photographs, taken by John Johnston in the 1890’s, are placed throughout the rooms of the home. Johnston, a native of Bolton, England, photographed each room of the Whitman residence. These photographs not only capture the cluttered life Whitman spoke highly of having, but also became significant for the restoration of the house in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Here is an example of one photograph, where the clarity of the wallpapers was utilized in creating period, Victorian-era wallpaper during the restoration process.

Whitman’s parlor room was refurbished and rejuvenated with the assistance of this photograph. Many pieces of the furniture were repaired and put into positions as seen in this photograph. Many of the photographs in the photo were copied and or retrieved and placed in their original position. Johnston even made comical remarks about having one of his photographs in this particular photograph, sitting with others on Whitman’s mantel piece.

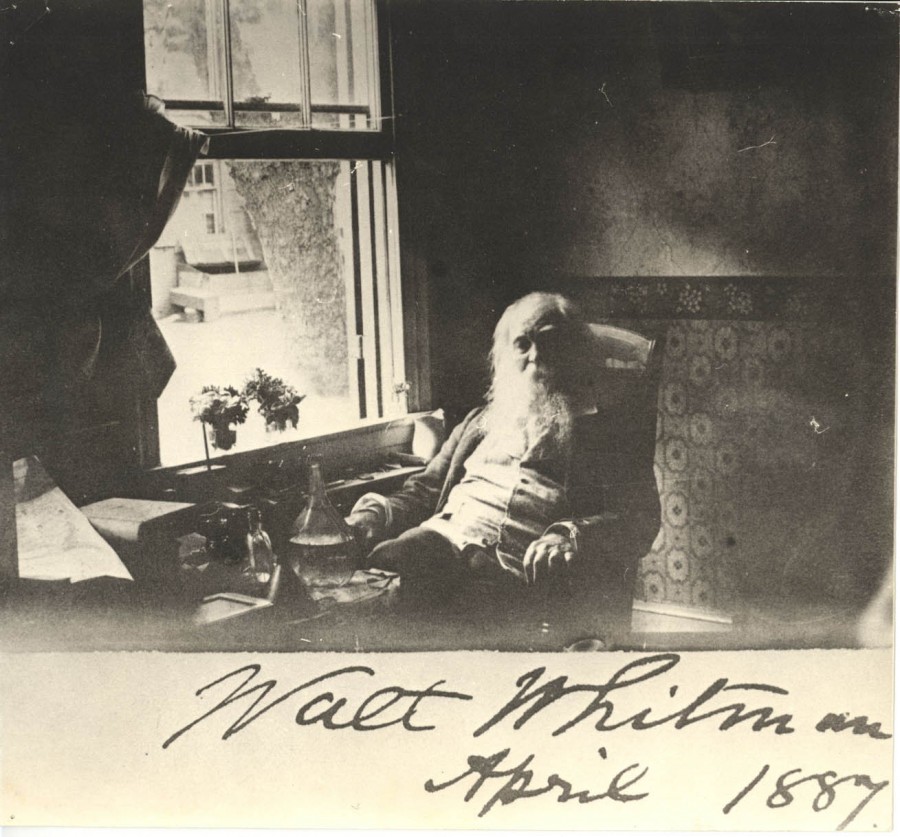

Another useful photograph of Whitman’s parlor room was taken by the renowned painter and photographer, Thomas Eakins, in 1891. His glass plate negative depicts the poets final years through the illumination of a window (Fig. 1).

Fig.1. Eakins, Thomas. “128.” Glass plate negative. (4 x 5in) 1891. Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. Walt Whitman Archive.

Whitman wrote, “A morning glory at my window satisfies me more than the metaphysics of books.” Surrounded in darkness, only the streets of Camden illuminate Whitman’s face, as well as two delicate flowers on the windowsill.

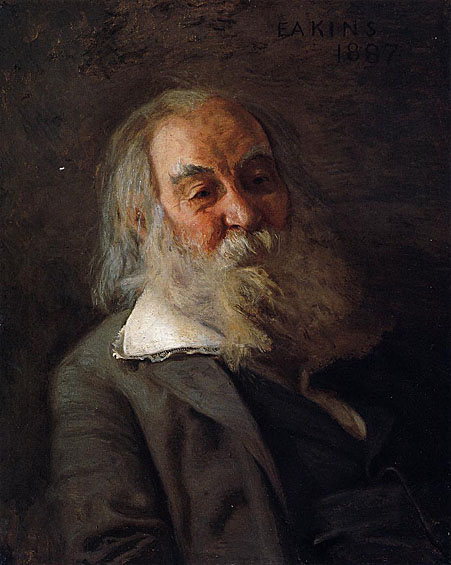

The Whitman house owns two original pieces that exemplify the poet’s fame and life history. A charcoal portrait of Whitman, drawn by his friend’s father, Maurice Traubel, hangs on the right wall of the entrance way as you enter the home. Placed by his magnificent image which captures Whitman in his old age, is the earliest recorded photograph taken of Whitman as a twenty-eight year old, traveling to different newspaper companies, in New Orleans. The charcoal sketch of Whitman is copied from Thomas Eakins’s Portrait of Whitman from 1888, (Fig. 2) which is presently located in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. No digital copy of the charcoal sketch exists; here is an example of the original work by Thomas Eakins.

Fig.2. Eakins, Thomas. ““Portrait of Whitman.” 1889. The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

The earliest photograph of Whitman hangs in his bedroom on the second floor, this piece was not owned by Whitman, but was donated to the Whitman House. Whitman is shown at the age of twenty-eight, with a serious expression and dressed in a dark frock typical to the time period (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Daguerreotype of Walt Whitman. New Orleans. February-May 1848. Walt Whitman Archive.

The Whitman daguerreotype’s photographer is unknown; however the framing of the photograph is in a mahogany-colored glass passe-partout mount, a typically European, specifically French design. Because Whitman never traveled to Europe, the photograph could be traced to New Orleans not only by the frame, but also from the “binder’s waste” seal located on the back of the daguerreotype.[14] The inscription states “Le Messager,” referring to a bi-lingual newspaper published during 1846 and 1860 in Bringier, New Orleans.[15] The relation between Whitman and the bi-lingual newspaper remain a mystery, however the prominence and prestige of Whitman’s career, even in his early years, is established through this photograph.

The Whitman house collection, along with period or originally Whitman owned furniture, conjoining with the accurate Victorian-period restoration combine to create an environment of memory, fundamental to the accessibility and success of Whitonian education. The entire atmosphere of the Whitman house constitutes a milieu de mémoire, encouraging the perpetual memory of history and its impact on the present and future.

Through various educational opportunities for all ages, the Walt Whitman house instigates a milieu de mémoire, through tours on site, an annual poetry contest, and an annual birthday celebration traditionally dating back to 1890. School tours shaped to target all age groups, with lesson plans for elementary, middle, and high school students posted on the Walt Whitman House website. College student touring takes priority of the foundation, with English and history students researching the life of Whitman in Camden. A high school poetry contest occurs annually in May, where students submit Whitman inspired poems for a reading ceremony every year. Encouraging education in active learning experiences is fundamental in any scholarly endeavor, and vital to the rehabilitation of education in the city of Camden. College students from across the nation frequently travel to the Whitman house in Camden. In the fall of 2009, a multi-campus digital experiment, “Looking for Whitman,” occurred across the campuses of four universities. Students from the New York City College of Technology, New York University, University of Mary Washington, and Rutgers University-Camden, created an online project used for to “share their intellectual experiences of exploring Whitman’s work in relationship to specific places in which Whitman lived. The website was used as a distributed space for sharing ideas, research, and feedback across these courses and campuses.”[16] The website included numerous essays, blog posts, and videos of various readings of Whitman’s poetry. The campuses ended their semester with a pilgrimage to the Whitman house in Camden, where their weeks of research and dedication culminated in a sacred-like journey to the home where Whitman spent his final years. Students expressed their journey of education, their newly found love for the great poet, and their inspiring visitation at the Walt Whitman house. Most significant in the enforcement of education and the creation of a milieu de mémoire, is the annual Whitman Birthday celebration on May 31. Whitman first celebrated his birthday in a Philadelphia restaurant, Reisser’s on 5th Street, on May 31, 1890, with a group of about thirty close friends.[17] These celebrations continued until and after Whitman’s death. On March 26, 1892, the day of Whitman’s death, crowds of people flooded the city of Camden to honor the great American democratic poet, as seen in details from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly.

Massive celebrations pursued the following days after Whitman’s death. Horace Traubel, Whitman’s devoted friend, continued to hold birthday celebrations for the deceased poet in the garden located in Whitman’s backyard, as does The Whitman Association today. These gatherings evoke a dedicative memorial experience that began 121 years ago, and will continue for years to come. These opportunities would not be possible without the devout Whitman enthusiasts, from the beginnings of memorializing Whitman in the 1920’s, to the avid members and workers of the Walt Whitman Association today.

The Walt Whitman house is a unique memorial, personifying the condition and future restoration of the modern City of Camden. Usually restoration projects of homes from the Victorian-era are for elaborate, luxurious upper-class mansions. The Whitman house is specifically a middle-class home, not in shambles, but modest in nature. The home emphasizes the ephemeral sentimentality Whitman’s poetry conveyed and yet speaks for Camden as well. The home was rejuvenated at first by devoted neighbors of Whitman, and then by state and national funding. Restoration allowed the Whitman house to give back to the community. Continued investment in the Whitman House as a part of the legacy of Camden produces educational and employment opportunities for the beleaguered city, one of the roots in which to revitalize the current deindustrialized and disinvested City of Camden.

Bibliography

About Looking for Whitman. Looking For Whitman. 2013. Web. 17 Mar. 2013.

Bethel, Denise B. “Notes on an Early Daguerreotype of Walt Whitman.” Walt WhitmanQuarterly Review. Vol. 9 (Winter 1992), 151.

Blake, D. Leo. Interview by Diana Maddison. Guided tour by curator of Walt Whitman House. 328 Mickle Street, Camden, New Jersey. 28 Mar. 2013.

Folsom, Ed and Kenneth M. Price. Walt Whitman. The Walt Whitman Archive, May 2008. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

Gillette, Howard. Camden After the Fall. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Ifill, L. Matthew. “We Do Not Entomb You or Bid You Farewell: Walt Whitman’s Last Days,

Last Celebrations and Lasting Tradition.” Conversations: Newsletter of the Walt Whitman Association. Spring/Summer 2011.

NJ Dept. of Environmental Protection New Release: Walt Whitman House Restoration Receives National Award. 21. Jun. 2001. Web. 23 March. 2013.

Nora, Pierre. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Colombia: Columbia University Press, 1996-1999.

Sill, M. Geoffrey. Mickle Street House. The Walt Whitman Archive., May 2008. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

Trubek, Anne. A Skeptic’s Guide to Writer’s Houses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Walt Whitman House. New Jersey Historic Trust, 1992. Web. 23 Mar. 2013.

Welcome. The Walt Whitman House, State of New Jersey, 2002. Web. 18 Mar. 2013.

List of Images

Eakins, Thomas.128. Glass plate negative. 4 x 5 inch. 1891. Camden. Hirshorn Museum and

Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, National Mall, Washington, D.C. Walt

Whitman Archive. Web. 15 March 2013.

Eakins, Thomas. Portrait of Whitman. Oil on canvas. 301/8 x 24¼ inch. 1889. The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA.

Johnston, John. Whitman’s residence, 328 Mickle Street, Camden, NJ. Photographic print.

4 x 5 inch. 1860-1890. Alderman Library, University of Virginia. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

[1] “Walt Whitman House.” The Walt Whitman House, State of New Jersey. Web. 18 March 2013. https://www.state.nj.us /dep/p arksandforests/historic/whitman/

[2]Walt Whitman. Leaves of Grass. Viking Press: New York, 1959.

[3]Camden in the 1950’s waterfront industry created a profitable community. Availability of work and shopping centers encouraged population and industrial growth. The city reached the population of 124,500 in 1950. Due to disinvestment, deindustrialization, and race riots, the city’s prosperity declined. Crime, poverty, and unemployment rose due to businesses leaving Camden for cheaper employment and manufacturing in the south and overseas. Today, Camden’s population is under 78,000 people. Revitalization of Camden is difficult due to crime and governmental economic priorities; however investments are made in museums and memorials, which provide education for its inhabitants and encouragement for relocation into Camden. (Dates and population numbers from: Howard Gillette. Camden After the Fall. University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 2006. Ch. 1-2).

[4] All dates in this summary of Walt Whitman’s life were taken from the thorough and informative: Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. “Walt Whitman.” The Walt Whitman Archive. 26 March 2013. https://waltwhitmanarchive.org/biography/walt_whitman/index.html.

[5] “Welcome.” The Walt Whitman House, State of New Jersey. Web. 18 March 2013. https://www.state.nj.us/dep/p arksandforests/historic/whitman/

[6] Leo D. Blake. Interview by Diana Maddison. Guided tour by curator of Walt Whitman House. 328 Mickle Street, Camden, New Jersey. 28 March 2013.

[7]Anne Trubek. A Skeptic’s Guide to Writer’s Houses. University of Pennsylvania Press, Pennsylvania: 2011.

[8] Geoffrey M. Sill, “Mickle Street House.” The Walt Whitman Archive.

[9] Leo D. Blake. Interview by Diana Maddison. Guided tour by curator of Walt Whitman House. 328 Mickle Street, Camden, New Jersey. 28 March 2013.

[10]“NJ Dept. of Environmental Protection New Release: Walt Whitman House Restoration Receives National Award.” Web. 23 March 2013.https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/releases/01_0076.htm.

[11] “Walt Whitman House.” New Jersey Historic Trust. Web. 23 March 2013. https://www.state.nj.us/dca/njht/funded/sitedetails/waltwhitmanhouse.html.

[12]“NJ Dept. of Environmental Protection New Release: Walt Whitman House Restoration Receives National Award.” Web. 23 March 2013.https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/releases/01_0076.htm.

[13] Pierre Nora. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Columbia University Press:1996-1999. 9.

[14] Bethel, Denise B.. “Notes on an Early Daguerreotype of Walt Whitman.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 9 (Winter 1992), 151.

[15] Ibid. 152.

[16] “About Looking for Whitman.” Looking For Whitman, 2013. Web 17 March 2013. http://www.lookingforwhitman.org/about.

[17] Matthew L. Ifill. “We Do Not Entomb You or Bid You Farewell: Walt Whitman’s Last Days, Last Celebrations and Lasting Tradition.” Conversations: Newsletter of the Walt Whitman Association. Spring/Summer 2011. 1.